It seems like we stand in the centre of the world. In the centre of our world.

From this place we can observe all. See sights. See situations. See people. Be drawn towards. Turn away. Fit.

From our vantage point, with our map of the world as the world should be, we can assess everything, place a value on it, judge it. We can rank things, place them in hierarchies of choice, want, need. We can compare this external vista of things, people and their actions with our perception of right and wrong, good and bad.

And we do…

We critique the behaviour, choices, necessities of others. We glance at the unsightly homeless person from the corner of our eye, thereby maintaining a dignified separation. We wince at the teenager’s language and lack of respect in the street, like we skipped that life stage. We place the drunk man in a story, a story of our own creation, so that we can explain his ‘condition’. We assess the parents and their actions towards their screaming toddler, like frustration, tiredness, learning are all experiences we have never had or at least have always handled better. We gossip about the neighbour and the affair we think they’re having, so that we can stay in the ‘moral’ club through our action of placing them in the ‘immoral’ one. We whisper with colleagues about the boss who seems oblivious to the impact of their actions, because there is safety in collusion. We mutter about the Sunday driver who meanders when we’re in a hurry to be somewhere, like they have no intent or purpose.

That person is good, this one less so. We’re OK, because they’re not. How can he do that? Why is she so…? Why don’t they…? I wouldn’t do that. Who wears that? Does she know what she looks like? Really … pink? Why doesn’t he wash his hair? Another holiday!? Why can’t she just say? He’s a waster. She doesn’t realise what she’s doing to him. Amazing, awful, not good enough, disgraceful, shameful, good heavens…

We all do it, every day. It comes easy. Too easy.

Maybe because in our map of the world, our view of right and wrong, of good and bad, we can be exonerated? We are innocent. Never guilty. We are successful. Never a failure. We are ethically and morally just. Never wicked.

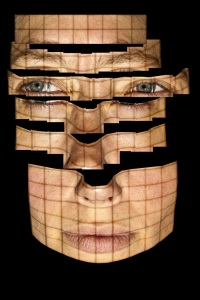

But maybe facing ourselves is merely the hardest direction to look?